Academic writing and publication are difficult enough for authors who have English as their first language.

For non-native English-speaking authors, writing in English can be a huge challenge. The English itself, more than the science, can make or break their chances of publication. It’s how you communicate your science, so it needs to be just about perfect.

With increased pressure on publication space and increased demands on editors’ time, many journals use language screening to check submissions before they reach the editor’s desk. Can you get by them?

Some editors quickly reject papers that they feel are poorly written. Their English filter is triggered at the first run-on or ungrammatical sentence. They may desk reject them or send a “boilerplate” message to have the English edited (and yes, we’re here to help with that).

But even in your English isn’t perfect, there are common scientific writing language errors you can avoid. Knowing these will improve your writing and increase its chances of being accepted for publication.

What you’ll learn in this post

• Why your English ability shouldn’t affect your ability to get published.

• How to think like a researcher so that your writing will be less of a burden.

• Common mistakes that non-native speakers of English (and even native speakers of English) make, and how to quickly fix them.

• The best solution for correcting your academic, scientific English.

Think like a researcher

Think of the writing process in the same way you think about performing experiments. You want to get results that avoid multiple interpretations. When the reader can easily and accurately understand the language, there won’t be multiple interpretations. In experiments, we use controls to rule out alternative hypotheses.

In language, we have to avoid ambiguities and unnecessary text to get our message across clearly.

Scientific writing should have the “three Cs”:

- Clarity – it’s clear

- Conciseness – it’s brief, not longer than necessary

- Correctness – it’s accurate

To achieve this, you need to be as brief and specific as possible. But you also can’t omit any key details that help the reader understand you.

In other words: write no more than you need to accurately convey your message.

Sloppy writing may be a case of too much rather than too little

Although writing that doesn’t do this is sometimes described as “sloppy” or “lazy,” often it’s because the author isn’t aware that the writing is unclear and ambiguous. They may be saying too much, or trying too hard to include every possible detail.

This makes it vital to understand the impact of your own writing. You can do this through getting others’ opinions and through carefully rereading what you wrote, from the reader’s perspective (not your own).

“Journal editors, overloaded with quality manuscripts, may make decisions on manuscripts based on formal criteria, like grammar or spelling. Don’t get rejected for avoidable mistakes; make sure your manuscript looks perfect.”

–quote from a senior executive at a large international publishing house

There are many common mistakes; more than we can possibly list up. But we’ve put together a few of the most common ones that non-native English-speaking authors make. We hope this helps.

Note that these all fail the 3 Cs. Always refer back to that standard.

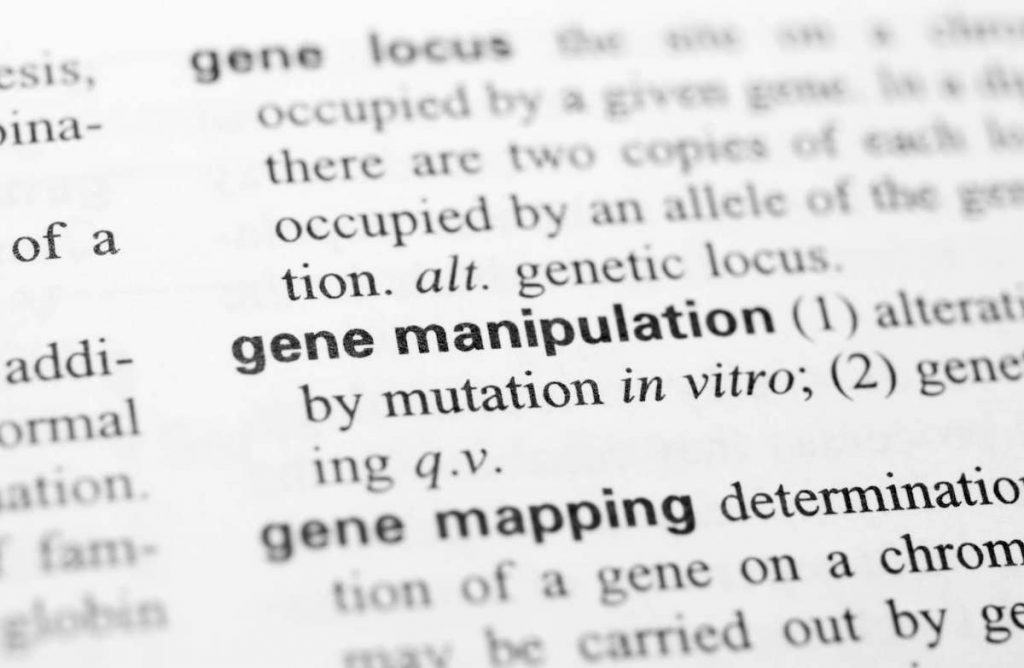

Protein and gene nomenclature

One very common cause of confusion is use of incorrect nomenclature to describe changes in the levels of genes, their mRNAs, or the proteins that they encode.

Constant changing from describing gene expression levels to protein levels and back again can also add to the confusion. Especially because the names are often the same.

You need to be completely clear to the reader exactly what level you’re talking about.

Effective English Writing

Get insights from a real journal editor!

This quick handy PDF highlights what to do (and what NOT to do) when writing your research manuscript.

Our experts show you how to write effectively for better readability and faster publication!

Using proper nomenclature

Nomenclature differs among species, but generally gene names should be described in italics. Protein names should be in normal font.

Case (upper vs. lower) is often used to distinguish between species. Generally, for mouse, rat, and chicken, gene names are spelled with an Upper-case first letter and the rest in lower case. For humans, primates, and some domestic species, gene names are in ALL CAPS (capital letters).

Descriptions of mRNAs generally use the gene name (levels of p53 mRNA), or you can refer to the mRNA “for” a given protein (levels of the mRNA for p53).

The word “expression” is usually used to describe gene expression and can create confusion when used to describe protein and mRNA levels.

Usually, when referring to proteins, you can simply replace “expression” with “level” (or “levels”).

Be aware of the correct nomenclature for your subject’s species. And make sure that everywhere you refer to a protein, gene, or mRNA by name in the text it’s completely clear which of those you’re referring to.

Examples:

- “Expression of the Igf1 gene was increased in our transgenic mice.” Using italics and the word “gene” eliminates any possible confusion.

- “The IGF1 mRNA levels were elevated in our patient group.” This sentence uses correct nomenclature for human genes.

- “The serum IGF1 levels were elevated in the transgenic mice.” It’s clear this is referring to the protein. Capital letters are appropriate in this case, even though the species is mouse. That’s because it’s the correct nomenclature for the mouse protein.

Comparisons

Comparisons are frequently made in the Results sections. Here, it’s especially important to compare “like with like.”

One common error non-native authors make is overlooking this simple rule and leaving the reader to assume what’s being compared.

- At best, the language will appear unnatural but the meaning clear.

- At worst, the reader will get the wrong meaning.

For example, the sentence, “We compared expression levels of p53 in smokers with non-smokers” should actually be “We compared expression levels of p53 in smokers with those in non-smokers.”

Another frequent error with comparisons is using relative terms (higher, greater, more, etc.) without a reference. In the sentence, “transgenic mice showed higher levels of cortisol,” it’s unclear what these levels were higher than. So you need a than clause, like “…than control mice.”

The reader might assume this automatically, but there may be other ways to infer it. That’s not good. Accurate scientific writing must aim to remove all assumption. You must convey to the reader exactly what you’re comparing. That’s because result comparisons are critical to their interpretation and, ultimately, to their significance.

Finally, the word “between” should be used for comparisons of two findings, but “among” should be used for comparisons of three or more.

Examples:

- “The levels of ubiquitinated proteins were higher in patients than in control subjects.” In this sentence, the than clause provides a reference for the term “higher.”

- “The levels of ubiquitinated proteins in patients were higher than those in control subjects.” Unlike in the first example, where patients and controls are on the same side of the comparing term – that is, they’re both mentioned after “higher” – here, patients and controls appear on either side of the comparing term. Therefore, it’s necessary to add “than those” to compare like with like.

- “There was no significant difference in the levels of ubiquitinated proteins between patients and controls.” The word “between” is appropriate here comparing two groups.

- “There were no significant differences in the levels of ubiquitinated proteins among AD patients, PD patients and controls.” The word “among” is appropriate for comparing more than two groups. (Note the change to the plural differences because more than one type of difference is possible with more than two groups.)

Respectively

Native and non-native English-speaking authors both often misuse “respectively.”

As with the topics above, its misuse can lead to confusion and ambiguity. It’s often clearer not to use “respectively” at all. But it can be useful for using fewer words where there are two corresponding lists.

Using “respectively” correctly

Respectively is quite useful in the sentence, “The latencies to withdrawal from a painful stimulus in control and transgenic mice were 3 s and 2 s, respectively,” meaning that control mice withdrew after 3 s and transgenic mice withdrew after 2 s.

When describing something much shorter than “The latencies to withdrawal from a painful stimulus,” such as average weights, you don’t need “respectively.” “Control mice weighed 20±3 g and transgenic mice weighed 17±2 g” is better than “Control mice and transgenic mice weighed 20±3 g and 17±2 g, respectively,” which contains one additional word.

Note that “respectively” can only be used to refer to two corresponding lists at one time, and can’t be used to refer to more.

Thus, the sentence, “The latencies to withdrawal from 5 g and 10 g painful stimuli in control and transgenic mice were 3 s and 2 s, respectively” is incorrect and impossible to understand.

Example:

- “The proportions of monocytes positive for CD163, CD7 and CD11a were 45%, 63% and 70%, respectively.” In this sentence, the “respectively” makes clear that the three percentages refer to each of the three markers, in the same order.

Commas, hyphens, and “which”

Used incorrectly, these three elements of writing can introduce ambiguities, and create potential for misunderstanding, in your writing.

Using commas and hyphens

In the sentence, “Because Aβ42 levels were elevated in 75% of AD patients in studies using our method [6,7], it is critical to obtain fresh samples,” moving the comma after “method” to follow “patients” (or adding a new comma there) would completely change the meaning.

Similarly, in “calcium-induced calcium release,” removing the hyphen completely changes the meaning of the sentence. With the hyphen, “calcium-induced” is a compound adjective modifying the noun “calcium release.” With no hyphen, “induced” is a verb describing calcium’s effect on calcium release.

Thus, it’s critical to use hyphens with such compound adjectives to avoid misunderstandings. However, you don’t need a hyphen to combine an adverb and an adjective. For example “highly intense staining” and “high-intensity staining” are both correct, but “highly-intense staining” is not.

Misunderstanding of -ly adverbs and hyphens is a very common error among native speakers, even in major publications. But that doesn’t make it right.

Examples:

- “Glutamate receptors mediated synaptic plasticity…” tells the reader that Glu receptors are involved in developing synaptic plasticity.

- “Glutamate receptor-mediated synaptic plasticity…” identifies synaptic plasticity involving Glu receptors as the sentence’s subject (note the change from plural to singular because “receptor” is being used in a general sense and not to refer to a single receptor).

Using “which”

The word “which,” when used incorrectly, can also create a lot of needless confusion. It’s often confused with the word “that.”

Both words introduce clauses that modify nouns, but “that” should be used to introduce defining or restrictive clauses and “which” should be used to introduce non-defining or non-restrictive clauses.

For example, in “the sections that were positive for GFP were subjected to cell counting procedures,” the “that” introduces a defining clause that defines exactly which sections were subjected to cell counting.

By contrast, in “the sections, which were positive for GFP, were subjected to cell counting procedures,” the sections that were subjected to cell counting are rather loosely defined. This possibly refers to sections described in the previous or recent sentences. The clause about GFP positivity provides the reader with additional information, but it’s not essential for understanding the sentence’s meaning.

Because “which” is used in this way, be sure it’s absolutely clear what the “which” is actually referring to. This could be whatever immediately precedes it (most common), or it could be the sentences’ main subject.

For example, the sentence, “microglia migrated to the site of the lesion, which was associated with increased levels of ED-1” is somewhat vague. That’s because it’s unclear if the “which” is referring to the lesion or to the migration of microglia.

If you ever have doubts about these types of sentences, rephrase them completely. Eliminate the doubts. To avoid ambiguity, the sentence about microglia could be rewritten as “migration of microglia to the site of the lesion was associated with increased levels of ED-1” or “microglia migrated to the site of the lesion, and immunohistochemical analysis revealed increased levels of ED-1 at this site.”

U.K. vs. U.S. English – that vs. which

A key thing to mention here is that “which” is commonly used instead of “that” in U.K. English. And in conversational English, they’re often interchangeable.

For example, you’ll commonly see sentences like “Use methods which lead to accurate results” in U.K. English. And in conversation, you’ll hear things like, “These are the things which we must be careful about.”

That doesn’t make them right. And if you run around correct everyone’s grammar, you’ll just annoy people.

It’s fine to have localized English and to “break” a few rules in these cases. In scientific language, however, it does matter. That’s because we can’t leave the reader with any doubt. We need to be precise. This is critical for your scientific communication. Here are some specific examples for scientific English.

Examples:

- “Data were normalized to the housekeeping gene actin, which was used as an internal reference…” Here, the “which” refers to actin, which is therefore the following clause’s subject.

- “Data were normalized to the internal reference housekeeping gene actin, revealing increases in the levels of…” To later refer to the analyzed data, “which” would be inappropriate and ambiguous.

Articles: singular vs. plural

Articles (a, an, the) are adjectives that modify nouns. If they’re used incorrectly the reader may wonder if you’re referring to a specific thing or to a non-specific item or category.

Worse, they could interpret the text incorrectly and make a wrong assumption. That’s not good.

Incorrect use of articles can also lead to confusion relating to singular vs. plural tenses.

Which article?

The definite article “the” should be used in conjunctions with a noun referring to a particular item or group of items (with plural or singular nouns).

For example, “the sections were then stained with H&E” implies that the sections you referred to in recent sentences were stained.

By contrast, the indefinite article “a” should be used in conjunction with non-specific nouns.

For example, “a section was then stained” infers that a single section, any section, was stained. “A” should only be used to refer to a single item or category, and shouldn’t be used in conjunction with plural nouns. So, saying “a sections” would be incorrect.

Asian authors frequently leave articles out of sentences making them sound awkward and unnatural. That’s what happens when omitting the “the” in “adenovirus was injected into the fourth ventricle.”

We’re not blaming you. Many Asian languages have no articles and/or singular and plural tense. It’s hard to learn these things! Some never do. That’s why we need editors.

Examples:

- “The antibody was injected into the hippocampus…” (articles required to specify a particular antibody, presumably already referred to in the text, and a specific hippocampus, belonging to a subject already described).

- “A new method of extraction was devised…” (“a” used rather than “the” because this statement introduces this method to the reader; therefore, it’s non-specific at that time. Once introduced to the reader, “the new method of extraction” should be used to refer to that method in the specific sense).

Singular or plural?

Nouns are used in the plural tense by adding an “s” to the end (in most, not all, cases).

When there’s no article, it’s sometimes unclear if the wrong tense (plural vs. singular) was used. For example, in the sentence “Acetyl group was added,” the reader is not clear whether the author means “An acetyl group was added,” or “Acetyl groups were added.”

So when referring to multiple items, use the plural to avoid confusion. Writers commonly forget this when describing figures.

So use “arrows” rather than “arrow” where there’s more than one in the figure. Likewise, use “solid bars” rather than “solid bar” when referring to a bar chart with multiple bars.

Examples:

- “We obtained a biopsy…” (describing a single biopsy).

- “We obtained biopsies from eight patients…” (no article necessary unless these biopsies were introduced to the reader, in which case they’d need to be referred to in the specific sense “We obtained the biopsies …”).

What to keep in mind to help your chances at publication

Keep the following points in mind and you’ll immediately improve the chance of getting your study published:

- Apply the 3 Cs (clear, concise, correct)

- Remove repetition and redundancy

- Pay attention to detail to be sure your meaning is as clear as possible in each sentence

- Keep sentences short and simple

- Reread and edit

There’s help when you need it

After all that, some writers naturally have better English writing and communication skills. This is a product of education, experience, and the individual. Edanz levels the playing field. Our expert editors retain your voice while fixing up the scientific English. This greatly reduces your chances of being rejected based on the quality of your English. Need an edit? See how we can help.